I watched the woman steal three dozen eggs and a sack of potatoes while my shotgun sat loaded behind the door, untouched. It wasn’t the theft that froze me; it was the way she wiped her eyes before she ran.

My father built this farm stand in 1958. It’s nothing more than a weathered oak lean-to with a tin roof, sitting at the end of a gravel driveway that used to be surrounded by cornfields. Now, it’s surrounded by subdivisions with names like “Oak Creek” and “Willow Run,” where the only oaks and willows were cut down to pour the concrete foundations.

For sixty years, there has been a metal lockbox nailed to the center post. Written on it in fading white paint are two words: THE HONOR SYSTEM.

You take what you need. You put the cash in the slot. Simple. That box put me through college. It paid for my mother’s hip surgery. It was a testament to a time when a man’s word was his bond and a neighbor was just family you hadn’t met yet.

But times have changed.

I hear it on the radio in my tractor. Inflation. Supply chains. The price of diesel is up. Fertilizer costs have tripled. And out here, where the factories closed down a decade ago and the new service jobs don’t pay enough to cover the rent, people are hurting. Really hurting.

I’d noticed the light pilfering for months. A missing tomato here, a jar of honey there. I ignored it. If you’re desperate enough to steal a tomato, you probably need the vitamins. But last Tuesday was different.

It was a gray, biting afternoon. The woman drove a sedan that sounded like it was coughing up a lung. She didn’t look like a criminal. She looked like a nurse, or maybe a teacher—tired, wearing scrubs that had seen too many shifts. I watched from the kitchen window, sipping lukewarm coffee.

She stood in front of the stand for a long time. She opened her purse and counted coins. She counted them again. I could see her shoulders slump. She looked at the prices written on the little chalkboard—prices I had already lowered twice, even though I was barely breaking even.

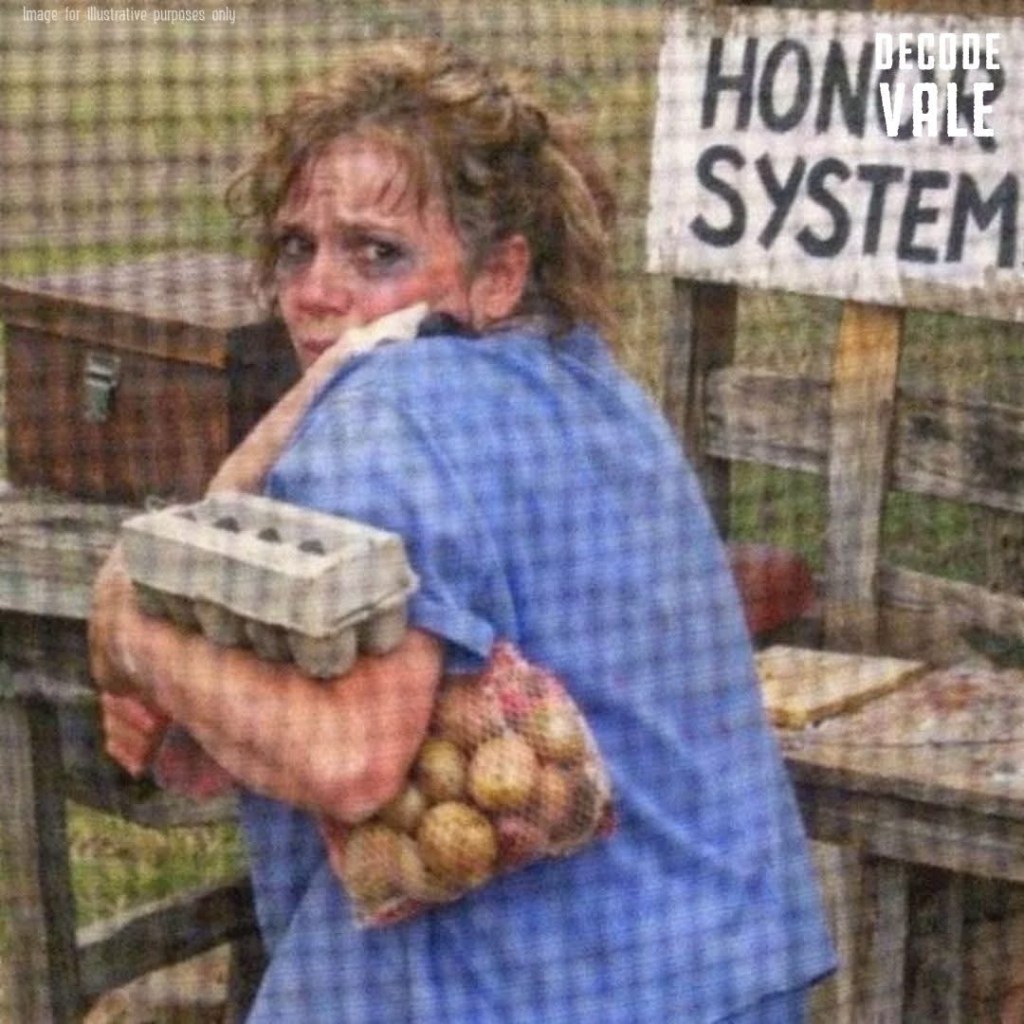

Then, she did it. She grabbed the eggs. She grabbed the potatoes. She moved fast, terrified, looking over her shoulder. She didn’t check the lockbox. She just threw the food into her passenger seat and sped off, gravel spraying against the “Honor System” sign.

My neighbor, frank, a transplant from the city who likes to give me unsolicited advice about liability insurance, was pulling into my drive just as she left.

“You see that, Beau?” Frank yelled, leaning out of his shiny truck. “I told you! You gotta get cameras. Or shut it down. People today? No morals. They’ll bleed you dry.”

I looked at the dust settling on the road. “Maybe,” I said.

“It’s the economy,” Frank grumbled. “Makes wolves out of sheep. Lock it up, Beau.”

I went inside. I looked at my ledger. I was in the red. Again. The logical thing to do was to close the stand. Or put a padlock on the cooler. Frank was right. You can’t run a business on good vibes and nostalgia.

But I couldn’t get the image of that woman’s slumped shoulders out of my head. That wasn’t the posture of a thief. That was the posture of a mother who had to choose between gas for the car and dinner for the table.

The next morning, at 4:00 AM, I went out to the barn.

I collected the eggs. I sorted the vegetables. Usually, I wash the potatoes until they shine. I polish the peppers. I make sure everything looks supermarket-perfect because that’s what the new people in the subdivisions expect.

Today, I did the opposite.

I took the biggest, most beautiful Russet potatoes—the ones that would bake up fluffy and perfect—and I rubbed a little wet dirt back onto them. I took the eggs that were slightly different shades of brown, the ones that were perfectly fresh but didn’t look uniform in a carton, and set them aside. I took the prize-winning heirloom tomatoes and found the ones that were shaped a little weird, the ones that looked like kidneys or hearts instead of perfect spheres.

I walked down to the stand and nailed up a new wooden crate right next to the Honor System box. I grabbed a piece of cardboard and a thick marker.

“SECONDS & BLEMISHED,” I wrote. “UGLY PRODUCE. CAN’T SELL TO STORES. 90% OFF OR TAKE FOR FREE IF YOU HELP ME CLEAR THE INVENTORY.”

I filled that crate with the best food I had. The “dirty” potatoes. The “mismatched” eggs. The “weird” tomatoes.

Then I retreated to the porch and waited.

She came back three days later. Same coughing car. Same tired scrubs.

She froze when she saw the new sign. She looked at the pristine, full-price vegetables on the main shelf, and then at the overflowing crate of “ugly” food. She approached it cautiously, like it was a trap.

She picked up a potato. She wiped a thumb over the smudge of dirt I’d carefully applied, revealing the perfect skin underneath. She paused. She looked at the house. I stayed back in the shadows of the curtains.

She didn’t run this time. She took a grocery bag and filled it. She took two dozen eggs. She took a bag of apples I had marked as “bruised” (they weren’t).

Then, she stood in front of the Honor System box. She didn’t have much, but I saw her put a crumpled bill in. It wasn’t the full price of the premium stuff, but it was something. She walked back to her car, not looking over her shoulder, but walking with her head up.

Over the next month, a strange thing happened.

The “Seconds” bin became the most popular spot in the county. It wasn’t just her. It was the old man from the trailer park down the road. It was the young couple who had just moved into the rental property. They’d pull up, read the sign, and load up.

And the Honor System box? It started getting heavy.

They weren’t paying market price. They were paying what they could. Sometimes it was quarters. Sometimes it was a five-dollar bill for a haul that was worth twenty. But nobody was stealing. Nobody was running.

One afternoon, Frank stopped by. He looked at the nearly empty “Seconds” bin and the few remaining items on the main shelf.

“You’re losing your shirt, Beau,” Frank laughed, shaking his head. “I did the math. You’re selling Grade A stock as garbage. I saw you put those peppers in there. Nothing wrong with them. You’re running a charity, not a business.”

“I’m not running a charity,” I said, leaning on my truck.

“Then what do you call it? You’re letting them take advantage of you.”

“No, Frank,” I said. “I’m letting them keep their pride.”

Frank went silent.

“If I give it away,” I explained, looking out at the cornstalks swaying in the wind, “they feel like beggars. If I let them ‘buy’ the ugly stuff for cheap, or help me out by ‘clearing inventory,’ they’re customers. They’re helping me out. It’s a transaction between equals. They get to feed their families without feeling small.”

Frank looked at the box, then at me. He didn’t say anything else about cameras.

Yesterday evening, I went down to close up the stand. The “Seconds” crate was empty, swept clean. The lockbox felt heavy. I opened it to collect the day’s take.

Amidst the dollar bills and coins, there was a small, sealed white envelope. No stamp. Just my name, “Beau,” written in neat cursive.

I opened it. Inside was a twenty-dollar bill—crisp, new. And a note.

“To the farmer, I know the potatoes aren’t bad. I know the eggs are fresh. I know what you’re doing. My husband got a job today. It’s not much, but it’s a start. We made a pot roast tonight with your ‘ugly’ vegetables. It was the best meal we’ve had in six months. Thank you for feeding us. But mostly, thank you for not making us ask. We will never forget this.”

I stood there in the fading twilight, the fireflies starting to blink over the fields. I held that twenty-dollar bill like it was a winning lottery ticket.

The economists will tell you that the Honor System is dead. They’ll tell you that in a dog-eat-dog world, you have to lock your doors and guard your hoard. They’ll tell you that kindness is a liability on a balance sheet.

But standing there, listening to the crickets and feeling the cool evening air, I realized they’re wrong. The Honor System isn’t about trusting people not to steal. It’s about trusting that if you treat people like people, they’ll rise to meet you.

I pocketed the note and walked back to the house. Tomorrow is another day. I need to wake up early. I’ve got a lot of perfectly good vegetables to go ruin.

Because hard times don’t create thieves; sometimes, they just reveal who is hungry. And true community isn’t about watching your neighbor through a lens; it’s about making sure their plate isn’t empty so they don’t have to steal to fill it.

Tears, this is so beautiful

LikeLiked by 1 person